Learn Tajweed of Surah Yaseen – Complete Guide for Proper Quran Recitation

Tajweed is the science of reciting the Holy Quran correctly, ensuring that every letter is pronounced from its proper place with its correct characteristics. Learning Tajweed helps preserve the original beauty and meaning of the Quran as it was revealed. On this page, you will learn the essential Tajweed rules in a simple and structured way, followed by their practical application in Surah Yaseen. This guide will help you improve pronunciation and apply Tajweed rules with confidence while reciting.

What Is Tajweed?

Tajweed means “to improve” or “to make better.” In Quran recitation, Tajweed refers to pronouncing each letter correctly from its proper place of articulation, giving every letter its rights and characteristics.

History of Tajweed:

The rules of Tajweed were developed to preserve the correct pronunciation of the Quran as recited by the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ. As Islam spread to non-Arabic speakers, scholars formalized Tajweed rules to prevent mistakes in Quran recitation.

Purpose Of Tajweed:

The purpose of Tajweed is to:

- Protect the Quran from incorrect pronunciation

- Preserve the beauty of Quran recitation

- Ensure every letter is recited correctly

- Avoid changing meanings due to pronunciation errors

Basic Rules Of Tajweed:

The basic rules of Tajweed help ensure correct pronunciation, proper elongation, and accurate stopping while reciting the Quran.

- Correct pronunciation of Arabic letters

- Applying elongation (Madd) properly

- Observing nasal sounds (Ghunnah)

- Stopping at correct places (Waqf)

1: Makharij al-Huruf (Points of Articulation)

Makharij refers to the points from where Arabic letters originate. Correct pronunciation depends on knowing these articulation points such as throat, tongue, lips, and nasal passage.

2: Sifaat al-Huruf (Characteristics of Letters)

Each Arabic letter has unique characteristics like heaviness, softness, clarity, or echoing sound, which must be observed while reciting.

3: Noon Sakinah and Tanween Rules:

Noon Sakinah:

Noon Sakinah is the letter ن with sukoon or occurring at the end of a word.

Tanween:

Tanween consists of double vowel signs (ــًــٍــٌ) producing a noon sound.

3.1 Ikhfa (Concealment)

When Noon Sakinah or Tanween is followed by specific letters, the sound is concealed with nasalization.

3.2 Izhar (Clear Pronunciation)

When followed by throat letters, Noon Sakinah or Tanween is pronounced clearly without nasal sound.

3.3 Idgham (Merging)

Idgham occurs when Noon Sakinah or Tanween merges into the next letter.

Idgham with Ghunna:

Occurs with specific letters and includes nasal sound.

Idgham without Ghunna:

Occurs without nasal sound.

3.4 Iqlab (Conversion)

Noon Sakinah or Tanween changes into Meem sound when followed by ب.

4. Qalqalah (Echoing Sound)

Qalqalah letters produce a bouncing or echoing sound when they carry sukoon.

5. Ghunna (Nasal Sound)

Ghunnah is a nasal sound applied mainly to Noon and Meem with shaddah.

6. Madd (Prolongation or Stretching)

Madd refers to extending the sound of letters. The length of prolongation varies depending on the type of Madd.

Types of Madd:

There are five types of Madd are following below:

- Madd Tabee‘i (Natural Madd)

- Madd Munfasil (Separated Madd)

- Madd Muttasil (Connected Madd)

- Madd Lazim (Obligatory Madd)

- Madd Aridh Lis-Sukoon (Temporary Madd)

7. Rules of Stopping (Waqf & Ibtida)

Waqf rules help determine where to stop or continue while reciting, without changing the meaning of the Quran.

Common Types of Waqf:

- Waqf Taam

- Waqf Kafi

- Waqf Hasan

- Waqf Qabih

- Waqf Mamnu

Listen to Surah Yaseen with Tajweed Recitation

Listening is one of the most effective ways to learn Tajweed. Below is a clear and slow recitation of Surah Yaseen with proper Tajweed, which will help you recognize the rules you have learned above. Try to follow along while listening and focus on pronunciation, elongation (Madd), nasal sounds (Ghunnah), and stopping rules (Waqf). If you would like to listen to Surah Yaseen in the voices of different renowned Qaris, you can also visit our Surah Yaseen reciters page to explore more recitations with proper Tajweed.

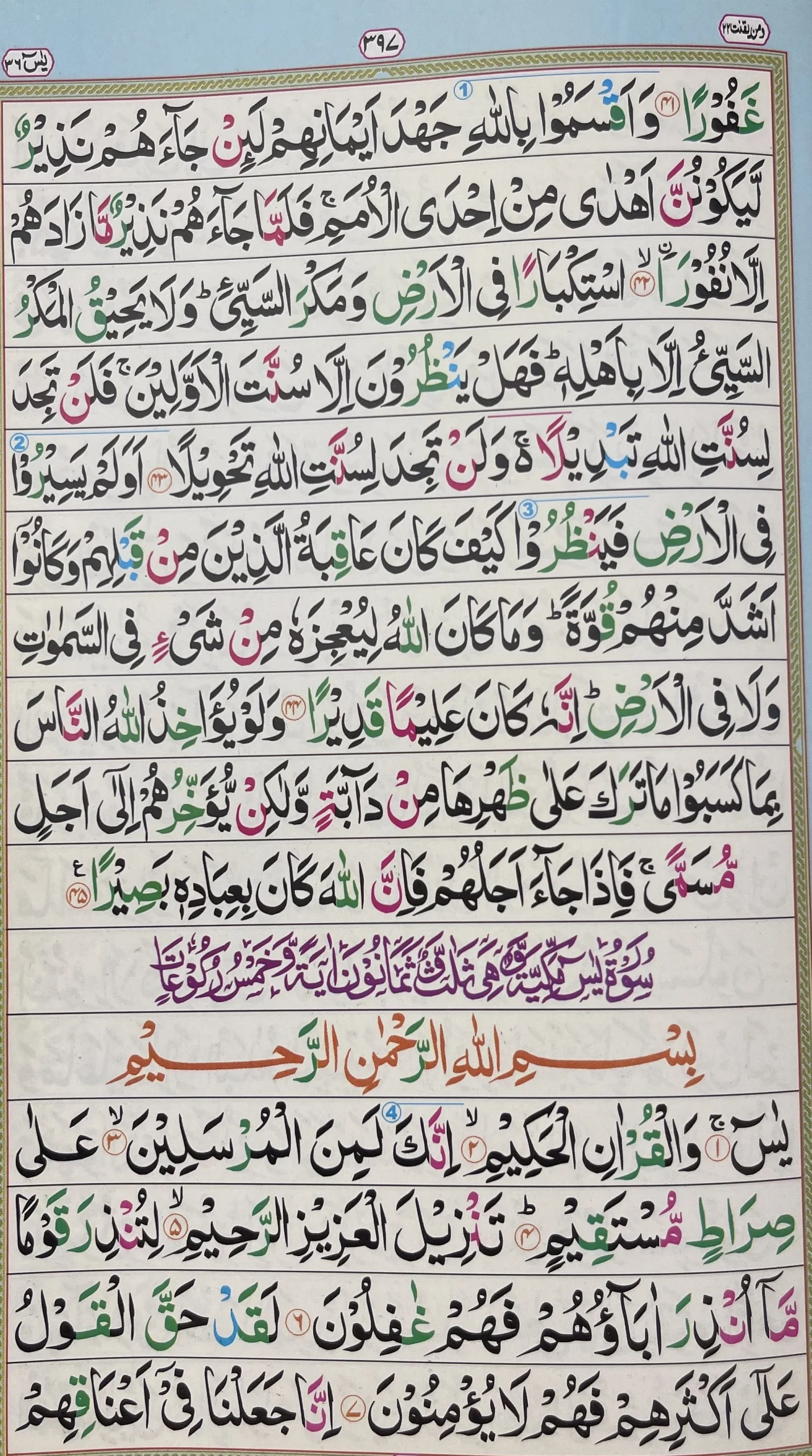

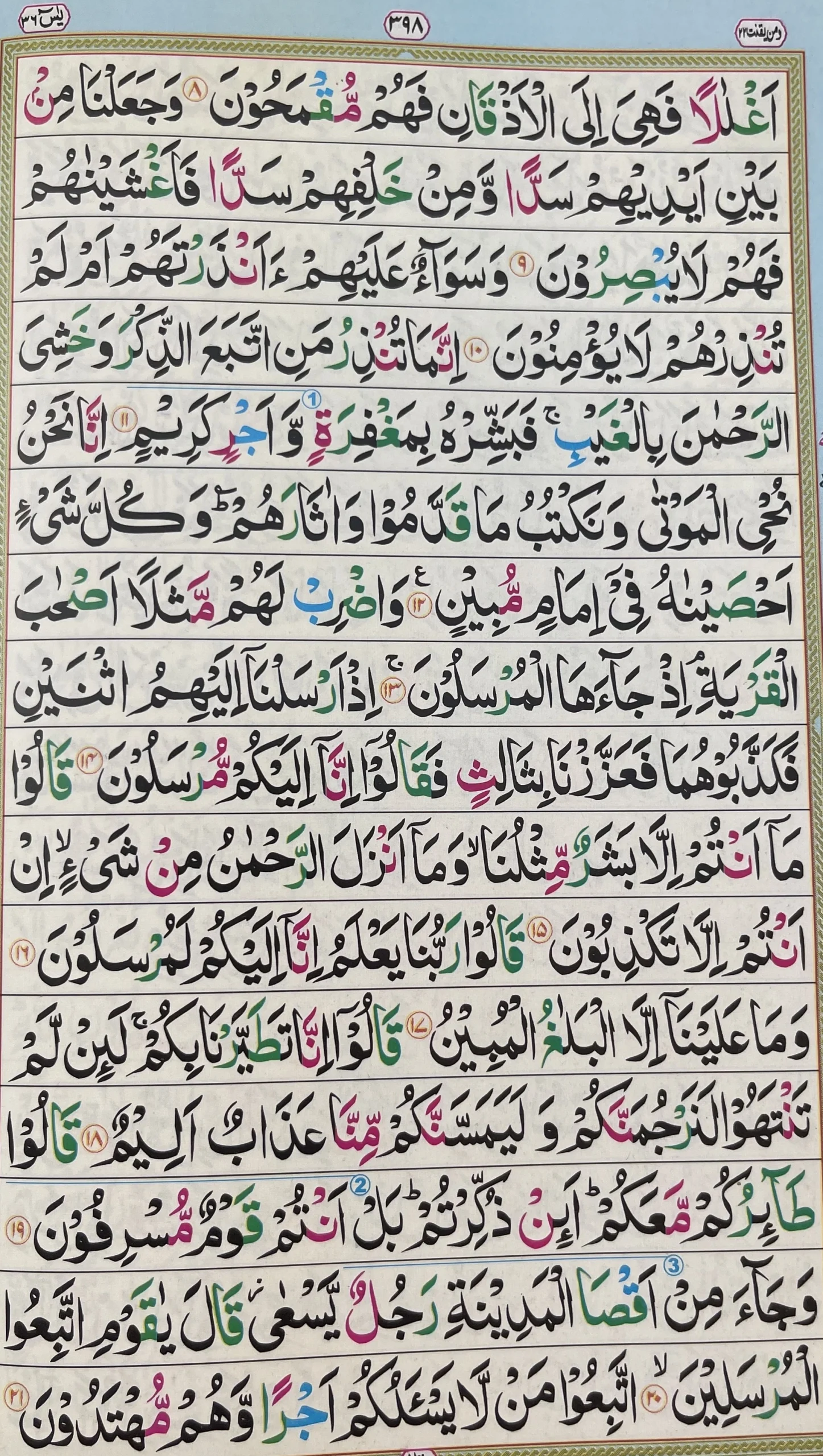

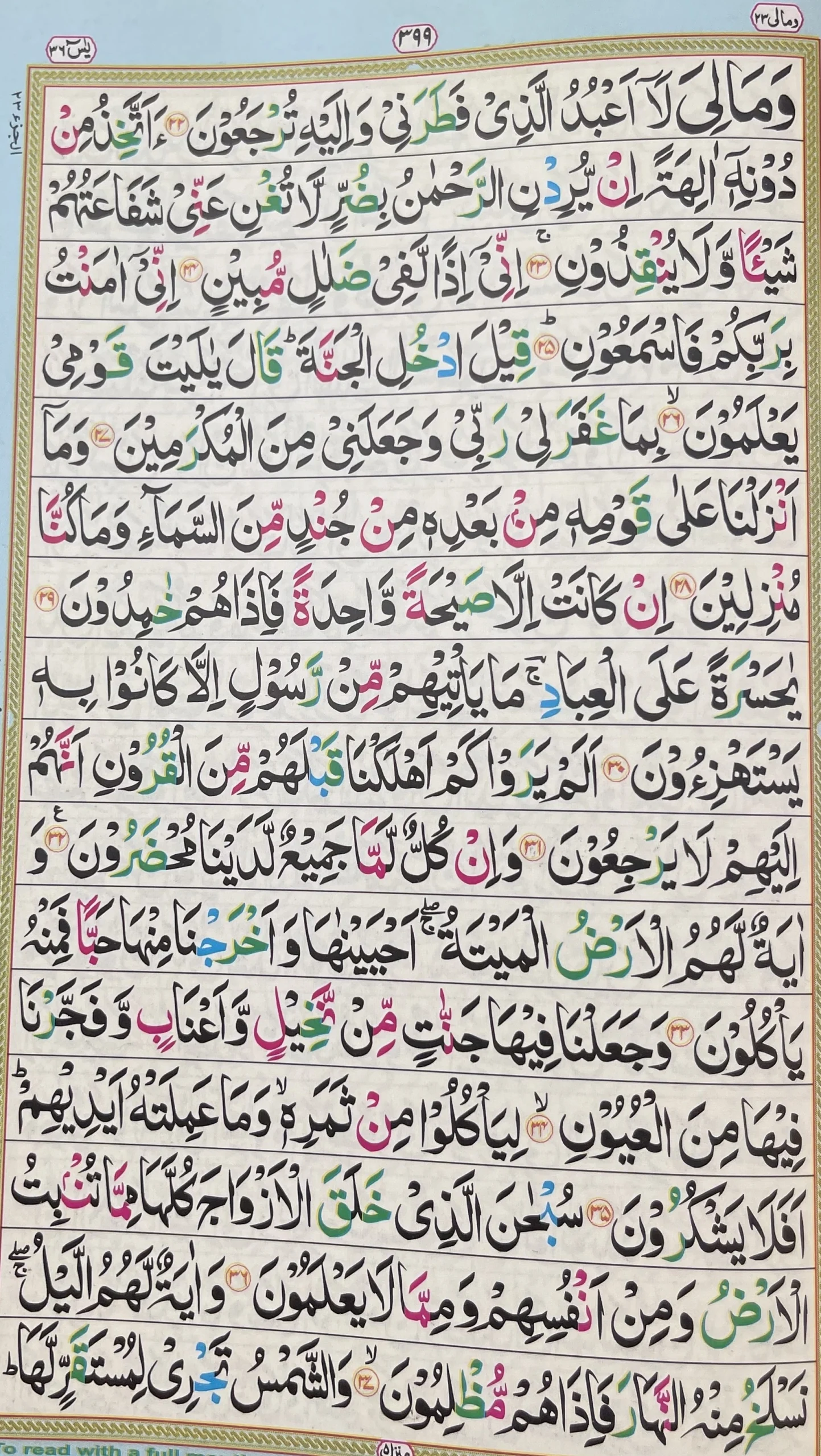

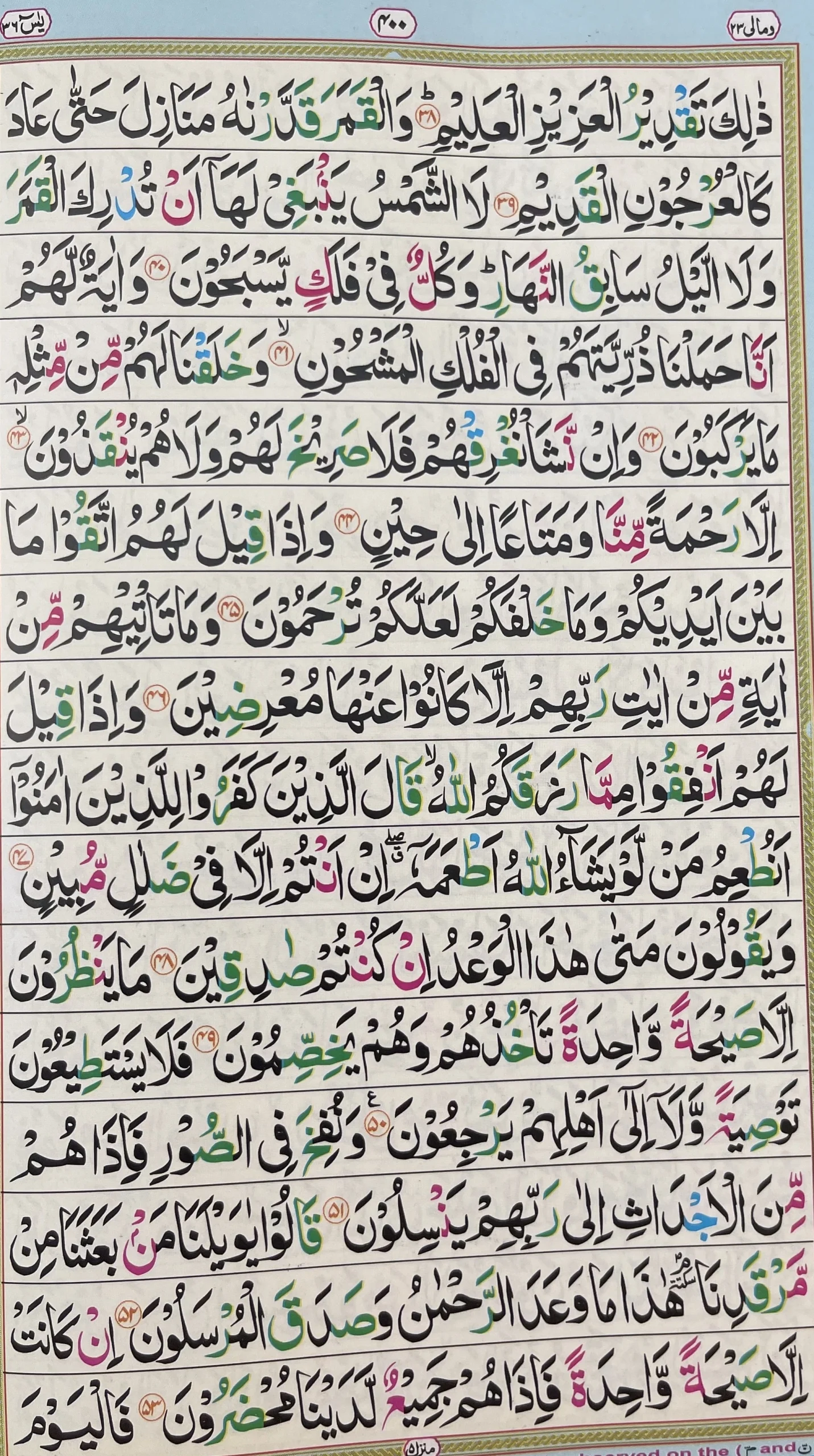

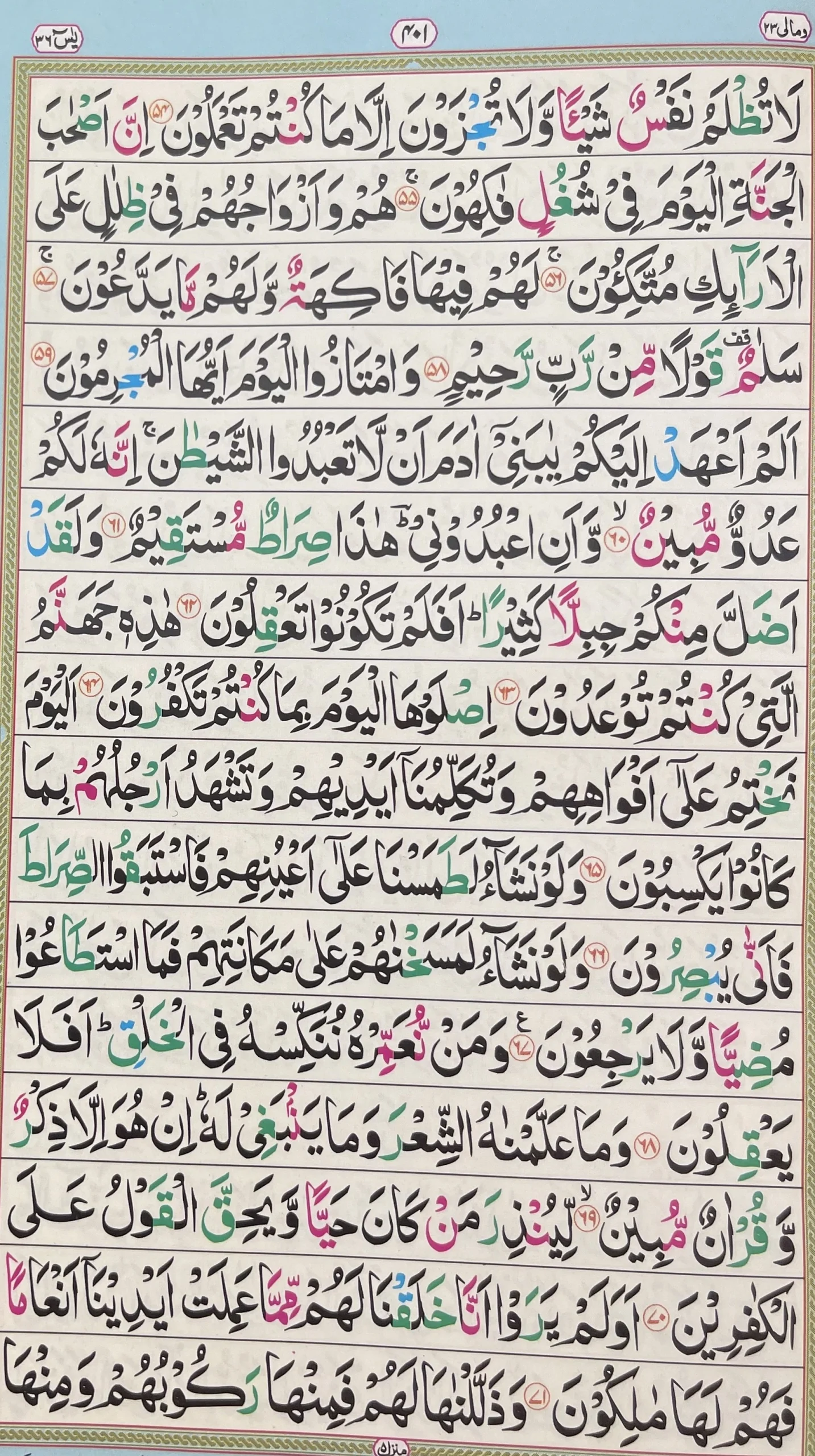

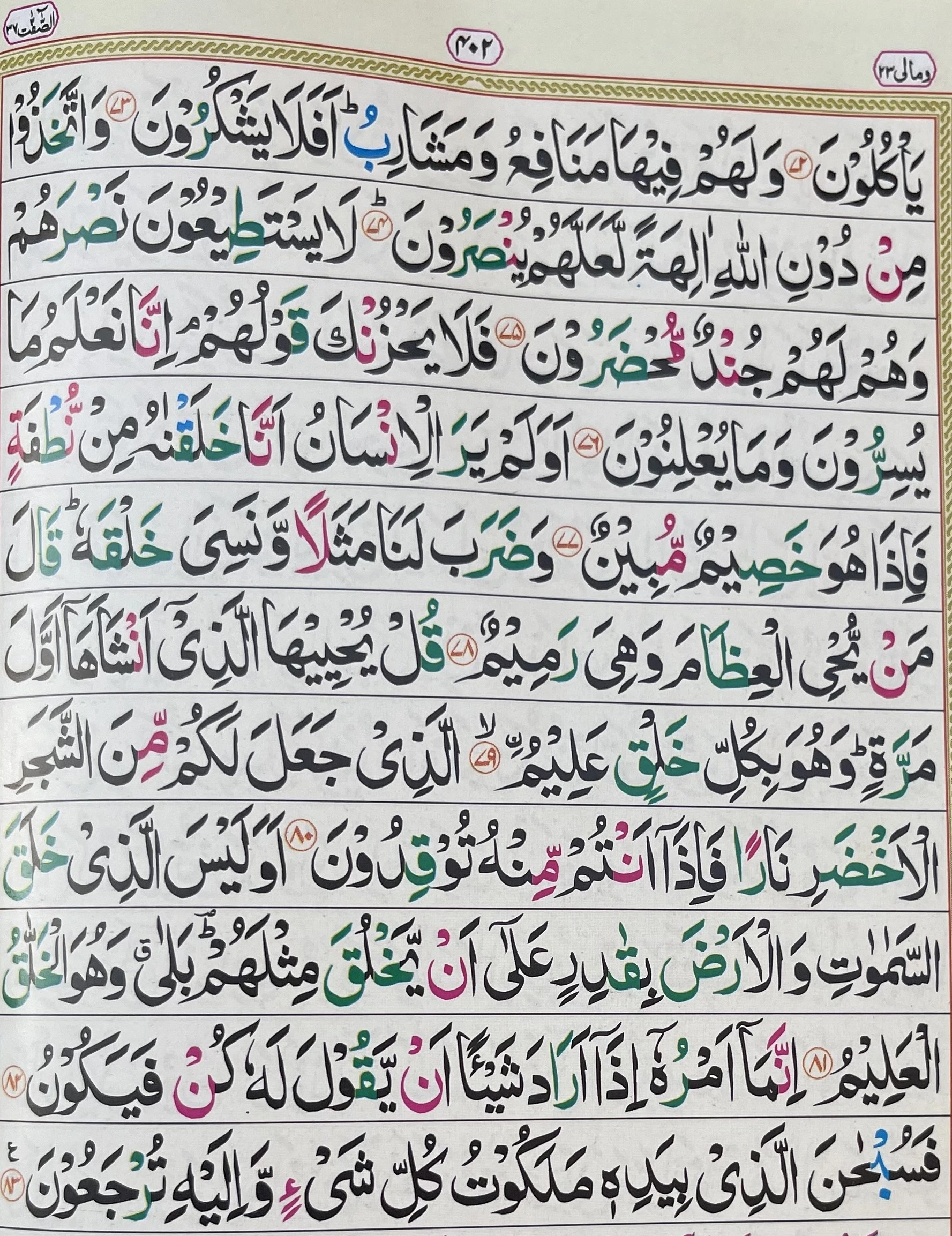

Surah Yaseen with Tajweed

Below are Surah Yaseen Tajweed images that demonstrate the practical application of Tajweed rules. The color-coded letters help you easily identify Tajweed rules while reciting. Take your time to observe each verse and try to apply the rules during recitation. If you would like to understand the meaning of the verses along with correct recitation, you can also read the Surah Yaseen translation.